Because it was a “sure thing” that the torrential downpour and fog blanket would continue the next day, naturally I opened my eyes at 6am, startled that the sun was beating down on me through the window. I leaped out of bed and into my damp shoes. Completely blue, clear sky. I thought I was gonna bomb around solo, but Derek woke up too while I was getting dressed and came along.

We could see where we’d been the day before! Without the visibility, the magnitude of the eruption that flowed over part of the town could not be understood. In the crisp dawn air, we climbed up on the hraun, and could see the line where the lava had claimed the ends of streets, where it had destroyed the water tanks, where it had built itself into a mountain and endangered the bay.

We could see where we’d been the day before! Without the visibility, the magnitude of the eruption that flowed over part of the town could not be understood. In the crisp dawn air, we climbed up on the hraun, and could see the line where the lava had claimed the ends of streets, where it had destroyed the water tanks, where it had built itself into a mountain and endangered the bay.

We were determined to get on the morning’s departing ferry, so we hurried (in fact, we hurried a little too much, and we lost each other for a time in the maze of hraun when Derek paused to photograph a cat and I ran too far ahead trying to see things fast). We crossed town and climbed a short steep hike for spectacular 360 views of Heimaey’s neighbouring inhabited islands, the volcanic cones and the hraun field of devastation, the colourful, cheerful town, wharf, and Iceland mainland across the water.

“The book” had warned that this hike got treacherous, as it wound around the cliffs where men hunt puffins by hanging from long ropes, swinging to and from the cliffs and snatching the birds off the rock. Traditional method: no harness, just a rope with knots in it. By all accounts madly dangerous, but still practiced on Heimaey.

We only went to where we could look over the edge of the cliff straight down on cream specks that were sheep grazing the edge of the golf course, took some pictures, basked in the sun, and then scampered back down to our hostel to eat and pack up, starving now from a few hours of moving at a clip and climbing.

We only went to where we could look over the edge of the cliff straight down on cream specks that were sheep grazing the edge of the golf course, took some pictures, basked in the sun, and then scampered back down to our hostel to eat and pack up, starving now from a few hours of moving at a clip and climbing.

We were escorted a few blocks to the Bakari by a large kitten (or small cat?) that was sweetly friendly. Bakari = bakery/cafe (although we saw a whole lot of bakari’s this trip, Heimaey’s was notably superlative). We’d already decided that cats formed a very strong presence in Iceland, and that observation was reaffirmed almost daily.

The ferry ride back across was a completely different animal. Smooth, picturesque; cute blunt-faced gulls later identified as guillemots wheeled around n the surf. When we docked, we more or less ran across the parking lot, determined to catch the ferry traffic as it drove off the boat. If all the cars got away without us in one of them, it was going to be a very long wait or a very long walk down the 30 some km ferry road.

I wasn’t used to Iceland hitchhiking yet.

The moment we reached the road and I spun around and threw out my hand, the next car, with two pretty women in it, stopped for us.

At this point we hadn’t really decided on our next destination. There were two choices- north towards Reykjavik, and south towards Vik. Vik=bay. Influenced by the fact our Finnish drivers were headed north, we decided to go to Hella with them, hitch from there to Landmannalaugar and embark on the four day Landmannalaugar to þórsmörk hike.

That’s about when I realized I’d completely forgotten the most important mission of yesterday- recovering my precious yellow notebook at the ferry terminal!! Alas. The day was not starting well.

That’s about when I realized I’d completely forgotten the most important mission of yesterday- recovering my precious yellow notebook at the ferry terminal!! Alas. The day was not starting well.

Hovering around Hella, scrounging for something to eat, reading the Lonely Planet’s warnings about this hike and contemplating buying four days of provisions at a gas station brought us around to the conclusion that Landmannalaugar was too ambitious for this day. Instead, we backtracked south again, aiming for Keldur.

Deposited at the turnoff to Keldur, 15 km away, we waited. There was a nice interpretive sign describing the historical site from Njal’s saga perfect for leaning our packs against. Other than the signs, there was nothing. Flat horseless fields, chilling, persistent winds, a grey overcast threatening to rain, and a long flat gravel road. Most pertinently, no cars. After zero cars took this turnoff for a half hour, we discussed walking, perhaps only to the stables four km away, whose roofs we could see. After 45 carless minutes, we debated other plans.

The day was not getting better. My hitchhiking experience tells me that anytime you have to wait a long time, someone special is coming to pick you up, or else there is something developing that you must be delayed in order to encounter. This idea was really tough to relax into though, after just arriving on a terribly exciting island with so much to do. Especially when cold and still damp, waiting for Godot at a drab intersection notable only for how unusually unscenic it was. It was already afternoon, and we hadn’t made it to a single “sight” yet.

Then, a speck appeared in the distance on our gravel road. After more minutes, the speck resolved into a walking person, which eventually became a blond girl walking in yoga pants. She was about to pass us without speaking, as though hitchhikers on a road that no one else seemed to want to travel was an everyday occurrence. When I spoke to her, she pulled out an earbud, told us she walked to the stables daily to unwind after work, and responded to my question about traffic frequency with a shrug. “Every few hours. There’s not much down there,” she said.

That did it. We relinquished Keldur and moved back to the ring road headed south.

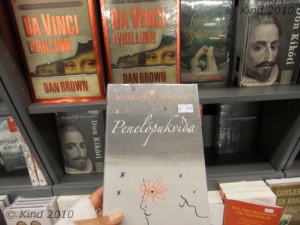

Another law of hitchhiking: as soon as you give up on something…. the very next car by turned down the road to Keldur. Arrrugh!!!! Just after that, though, we got a ride from a Spanish couple who were very nice but we could hardly communicate with. They got out and repacked their small 4×4 to fit us in, and as he drove, she wrestled with a huge detailed road map that we envied very much. In fact, we never ever found one like it for sale, and we really could have used one like it many times. They were clearly hunting for something we couldn’t help them at all with, and they only took us a short ways, but we quickly got another ride from a Torf (“turf”) farm worker and fisherman who was very knowledgeable and helpful. He was going way past the Westmannæyar turnoff, so I let go of returning to the ferry to get my notebook. Instead, the young Icelander drove us right into a different weather system and brought us to Seljalandsfoss.

Seljalandsfoss is a glorious waterfall visible from the highway and visited by hundreds daily. Its loveliest characteristic is that the water freefalls into a pool carved out of the rock that has abundant room behind it to walk right around under and a behind the roaring foss (falls). No cramped, crouching path, either, a thoroughfare with plenty of headroom. The day was looking up! The sun was shining now, and Seljalandsfoss was at the head of the road to þórsmörk. Our new mission was to head for þórsmörk and do the much shorter hike to Skógar.

Seljalandsfoss is a glorious waterfall visible from the highway and visited by hundreds daily. Its loveliest characteristic is that the water freefalls into a pool carved out of the rock that has abundant room behind it to walk right around under and a behind the roaring foss (falls). No cramped, crouching path, either, a thoroughfare with plenty of headroom. The day was looking up! The sun was shining now, and Seljalandsfoss was at the head of the road to þórsmörk. Our new mission was to head for þórsmörk and do the much shorter hike to Skógar.

We trotted further down the road after absorbing the main attraction and hunted out the lesser-seen foss, Gljúfurárfoss, in the back of a lush field behind the very well-appointed camping site Hamragarðar. This foss had carved a canyon out as it retreated into the shelf of rock it fell from, so that now, you can only see the water falling by taking your shoes off and walking in the stream through the narrow gap the water has eroded over millennia. Or you can climb the goat path, using the ropes and ladders provided, and even scramble the last wall of rock, knobby as a climbing gym wall, to look straight down into the shaft that the strand of water currently drops into. Breathtaking! The mist prisms the sunlight into a thousand tiny sparks and the sound of the water striking the bottom many metres below spirals up at you in a roar.

Thrilled with today’s discoveries, we peacefully got on the road to þórsmörk. The sun was warm enough to get down to a t-shirt. There were some sheep who came and looked at us. There was a bridge over the stream to practice balance walking on. We could watch the tour buses in the distance arriving at and leaving Seljalandsfoss at exact intervals, and there were other entertainments. We could see the mouth of the Gljúfurárfoss canyon, and sound carried well enough for us to get the gist of what the four young men approaching the stream were planning. Especially when three of them started stripping off their clothes. They were speaking another language, my guess Italian, but the top-of-the-lungs bellowing that started as they disappeared over the bank was unmistakable swearing, with unmistakable cause. That water was glacial. We weren’t too far away, either, to hear the sustained laughter of the fourth guy, who opted to climb the goat path instead. The laughter (his and ours), continued as three semi-naked, shrieking and swearing men raced to their car, snatching up shoes and clothes on the run and practically hurling themselves in.

Thrilled with today’s discoveries, we peacefully got on the road to þórsmörk. The sun was warm enough to get down to a t-shirt. There were some sheep who came and looked at us. There was a bridge over the stream to practice balance walking on. We could watch the tour buses in the distance arriving at and leaving Seljalandsfoss at exact intervals, and there were other entertainments. We could see the mouth of the Gljúfurárfoss canyon, and sound carried well enough for us to get the gist of what the four young men approaching the stream were planning. Especially when three of them started stripping off their clothes. They were speaking another language, my guess Italian, but the top-of-the-lungs bellowing that started as they disappeared over the bank was unmistakable swearing, with unmistakable cause. That water was glacial. We weren’t too far away, either, to hear the sustained laughter of the fourth guy, who opted to climb the goat path instead. The laughter (his and ours), continued as three semi-naked, shrieking and swearing men raced to their car, snatching up shoes and clothes on the run and practically hurling themselves in.

We waited. We made pita bread sandwiches and waited. The afternoon was getting late, but the difference here was that there was traffic. Pretty regularly, a vehicle every ten or fifteen minutes. Most of them were very impressive Hummer-ish trucks with huge tires, roof racks and exterior mounted lock boxes. Straight out of Indiana Jones style. This did not, however, alarm us one bit.

And then, a Suzuki nearly screeched to a halt by us. It was the Spanish couple! We were old friends now, and they’d already made room for us in their little truck. We were going to þórsmörk. “Yes, yes, þórsmörk.” In moments we bounced off the paved road onto gravel, barely slowing to ignore the sign that admonished only 4×4 vehicles should pass this point, and river crossings were inevitable. This guy drove like an Australian in a hurry. I can’t say I’ve ever been in a car with an Australian, but I imagine an outback driver jouncing around with the contents of the truck smashing from one side to another, all the while talking a streak like XXXXXXX. We were nicely wedged in with our packs on our laps, but still, this drive was impressive. Derek and I grinned at each other, and I was thrilled with this ride totally outside of my realm of hitchhiking experience.

And then, a Suzuki nearly screeched to a halt by us. It was the Spanish couple! We were old friends now, and they’d already made room for us in their little truck. We were going to þórsmörk. “Yes, yes, þórsmörk.” In moments we bounced off the paved road onto gravel, barely slowing to ignore the sign that admonished only 4×4 vehicles should pass this point, and river crossings were inevitable. This guy drove like an Australian in a hurry. I can’t say I’ve ever been in a car with an Australian, but I imagine an outback driver jouncing around with the contents of the truck smashing from one side to another, all the while talking a streak like XXXXXXX. We were nicely wedged in with our packs on our laps, but still, this drive was impressive. Derek and I grinned at each other, and I was thrilled with this ride totally outside of my realm of hitchhiking experience.

The road faded into more of a suggestion, as it was all chunky riverbed gravel. The truck bounced up and down and plunged again and again down the banks of small rivers and up the other side. His wife was totally serene, and the two of them looked over their shoulders over and over to piece together chat. We learned he was a professional photographer. They were questing for a glacier, and they’d been trying to reach it all afternoon.

The road faded into more of a suggestion, as it was all chunky riverbed gravel. The truck bounced up and down and plunged again and again down the banks of small rivers and up the other side. His wife was totally serene, and the two of them looked over their shoulders over and over to piece together chat. We learned he was a professional photographer. They were questing for a glacier, and they’d been trying to reach it all afternoon.

The river crossings grew wider and deeper. Unfazed, our driver drove fearlessly into each one, making water spew up over the windshield and come up the doors. He turned to tell us “rental car”. The surroundings got more and more desolate. Occasionally we stopped and our driver got a camera out of the back with a lens the size of a bazooka to take a couple shots.

We could see civilizationö houses flecks at a great distance to the left. It became apparent that we were driving through a vast river delta, several km wide, and the track we were following meandered across all the streams headed for the sea from the distant glaciers.

As we started to feel dwarfed by the landscape and more and more in the middle of nowhere, I was increasingly pleased with our fantastic luck to be in this great ride with an intrepid driver in a perfect little 4×4, making this startling journey into the unknown. Nevertheless, here in the unknown, there were still sheep, chewing their cuds and gazing at us like we were crazy.

As we started to feel dwarfed by the landscape and more and more in the middle of nowhere, I was increasingly pleased with our fantastic luck to be in this great ride with an intrepid driver in a perfect little 4×4, making this startling journey into the unknown. Nevertheless, here in the unknown, there were still sheep, chewing their cuds and gazing at us like we were crazy.

About 10km into this adventure, the road forked at a sign, and our hosts stopped to confer. We were near Gigjökull, a finger of Eyjafjallajökull. After map consultation and conferencing, the man turned to us, pointed to the right fork, said “we go,” and “you stay here.”

With startled consternation, my brother and I looked at each other. I went through the motions of thanking them profusely with a forced smile as I clambered out with my pack, inwardly gripped with worry. I’d be damned to have come so far and retreat now, but we were officially in the middle of nowhere, halfway between there and back, and our hosts were unflappably abandoning us. Suddenly they seemed like cruel, heartless people. They knew all along they weren’t going to þórsmörk, and yet, they had driven us into the void. In retrospect, the language barrier was too great to distinguish “to þórsmörk” from “towards þórsmörk”. So there we were.

They rumbled off, and there we were, standing next to a fast-flowing translucent river grey with silt. Tire marks drove out of the water on the opposite bank, headed to þórsmörk. After some exclaiming about this unexpected turn of events, I changed to my sandals and strode into the river (Note: river-fording instructions always command that you wear your hikers to protect your feet and ankles. Foolish though it may be, I was determined that the comfort of dry boots, so recently recovered, was too important to sacrifice, and I’d sooner go barefoot into the water. But one should wear boots when crossing rivers. What I say, not what I do). Two steps in and I realized the water was deadly cold. A third of the way across I realized how dangerous it would be to fall. The water was moving so fast and strong when you lifted your foot you had to hard fight the water pulling it away, and at the bottom the water was flipping over big stones that could roll on your feet. Half way across it got quite scary, rolling over my knees. With relief, I made it, dropped my pack and immediately headed straight back across before my feet could get going with screaming at me. I figured I’d help my brother, as a four legged beast would fare better than two, and I didn’t plan on standing by and watching him flounder if he fell, despite his shocked protestations that I was coming back across. He was also carrying the ultra-valuable camera. This time, I fell halfway. I went to all fours, the water dragging at my arms and feet like a wild animal, but I crab-walked a little, recovered, and made it to Derek’s shore. We rested, made a game plan, and then started to ford together holding onto each other. Again halfway, Derek got in a bit of trouble, and although I could barely stand myself, feeling nothing below my knees, I kinda helped him balance his pack and he got back to his feet and crossed. It was absurd luck I made it the first time.

Phew. We looked back at the innocently smooth flowing water, 30 feet width of quietly stealthy danger. Only an unknown further number of fords between us and þórsmörk!

Now we were definitely committed to our goal. We could see it, in fact, a small red roof where the mountains rose up again from the edge of this great rock and sand delta, I reckoned 6km away. We were very lucky. Both of us had legs and arms both soaked, but happily, our packs were bone dry, and our torsos mostly so, so we kept some core heat. We changed quickly, put on toques, and draped all our wet gear over our packs to hopefully dry out a little in the sun as we walked barefoot along the road as the sun dipped towards the earth behind us, laughing at the pure absurdity of all this.

After we’d gone a kilometer or so through the hugest empty space I’ve ever felt, holding only us, silence, and the background purring of water on the move, a vehicle came along behind us. We watched it approach with delight, and I prepared a self-deprecating grin on my face to counteract our drowned-rat appearance, totally confident in the common humanity that makes people help each other in distress, totally confident that this jacked up truck would stop to help us.

It roared right by, barely swerving to avoid us.

We kept walking, slapping along like Gollum, still dripping, but with feeling returning. This time, as we had miles of visibility, we could watch the unhelpful truck bounce along, revealing the route, and judging by his speed, gauge how far we were from that red roof. It was still, optimistically, 6km away. We would not make it by dark.

The next vehicle stopped. It was kind of awing that even out here, there were still trucks coming. This one was a very nice Pathfinder with EU plates driven by an Italian tourist who clearly did not want to take us on board. I understood, as we were going to leak all over his leather interior, but we really needed a ride. He pointed at the hut we were headed for and said “2km, walk”. I said “No, 6km,” and climbed in. I started chatting and charming for all I was worth to make up for imposing ourselves on him, and he warmed up. We encountered more rivers, and they were still getting bigger and deeper. This man was cautious, but determined, and we kept on crossing the fords as I praised and exclaimed and offered encouragement. It really looked like we were going to make it.

Then it got gnarly.

The red roof we’d seen, over 6km away as it turned out, was Húsadalur, still 3km shy of þórsmörk, and the river between us and it wasn’t conceivable to cross. It was thundering, dark, and deep. Húsadalur was totally cut off. Past Húsadalur, the rivers became more frequent, and the river rocks were getting much bigger. This made for a rougher ride, and scarier climbs out of each crossing as the tires strove to purchase on the grapefruit sized and up, round rocks. Worst of all, the track disappeared. Each crossing was only indicated by tire tracks leaving the water on the other side, telling that at least one other driver had made it, and was often hidden when the route is actually driving up the middle of the river to a place where you can get out. Now the rocks were hiding the tracks, so the route became guesswork. Several times he stopped, and we walked in three directions, looking like trackers for tire marks in a patch of sand that revealed the next stage, sometimes backtracking to find the ford.

When we got close enough to see þórsmörk, we started looking for the ford across the main river, peering at our Lonely Planets in our respective languages, and seeking the pedestrian footbridge mentioned therein. There was some long wooden structure on the opposite bank, but it was clearly not a bridge, and the river was formidable and 100 feet wide. I’d have sooner walked into Niagara. We could SEE the þórsmörk hut and its promised hot pools on the other side, but it was utterly unachievable.

An enthusiastically adventure-tour branded Hummer came along, shouted unhelpfully and incomprehensibly at us, and another arriving tour guide, with much angry gesticulation, managed to communicate that he was going back because it was hopeless. Our Italian wasn’t going back. We stopped at the clear end of the road, where the last tracks disappeared into the water at a hopefully wide (and therefore the shallowest) place. Here the mountains were starting again, a craggy field of badlands rising up from the edge of the river. We unpiled from his truck and peered together at the hut across the expanse of water. There were cars on the other side! Cars! How did they get there? I could see the Italian thinking “if they got there, I can”, but it wasn’t possible. I ventured into the nearest marshy shallows of the river far enough to know for sure it was undriveable, and even if we could make it through waist deep parts, we’d never survive that exposure. It was half a km wide of water.

He decided to wait for someone else to come. Why, I wasn’t sure. We’d definitely bonded by now, but still, we were ticks hitching on his mission. I felt like we’d worn out our welcome, and we should shove off and make our own way now. The sun was setting now, the temperature was dropping, and if we were going to camp in this wasteland, we needed to find a place and set up with some light. Derek and I agreed to do this, and I explained our plan to our driver. He looked at us with some alarm, asking where we were going repeatedly. I would gesture sweepingly at the mountain beside us with a big smile and he would frown. He was clearly unconvinced this was an attractive option, but he was also ok to be rid of us, and accepted it. He’d be ok, perhaps he’d sleep in his truck; but first he’d wait for another vehicle.

After goodbye, we plunged headlong into the brush and started clambering up the hill, slowed by the deep sandy volcanic ash and dense brush, aiming to make it over the shoulder of this small mountain and find someplace sheltered and flat to camp. Near the top, another entertainment began below us, and we stopped to rest and watch.  A giant yellow tour bus was approaching. It was clearly adapted for the drive, with impressive clearance and tires. It stopped below us, and the entire contents spilled out, too far away to hear but clear enough to see, taking pictures, smoking, and scurrying into the bushes. The driver conferred with our driver friend for some time. Then the bus swallowed everyone back up, and started to roll. I started to film, sure I was going to have a YouTube hit in the next 5 minutes. The bus went straight into the water, driving smoothly …. and disappeared around the corner of the hill/mountain we’d almost crested. What? We didn’t expect to lose sight of it. We “ran” to the top, reached it out of breath, looked over, and there was no bus. It had utterly disappeared.

A giant yellow tour bus was approaching. It was clearly adapted for the drive, with impressive clearance and tires. It stopped below us, and the entire contents spilled out, too far away to hear but clear enough to see, taking pictures, smoking, and scurrying into the bushes. The driver conferred with our driver friend for some time. Then the bus swallowed everyone back up, and started to roll. I started to film, sure I was going to have a YouTube hit in the next 5 minutes. The bus went straight into the water, driving smoothly …. and disappeared around the corner of the hill/mountain we’d almost crested. What? We didn’t expect to lose sight of it. We “ran” to the top, reached it out of breath, looked over, and there was no bus. It had utterly disappeared.

Our view, though, was straight into Goðaland, the land of the Gods. Countless towering rock forms like badlands making faces and bodies and creatures of every kind in their caves and complex shapes. It was amazingly beautiful, but the light was so poor now that we did not get very good photos of the complicated texture of the forms, and we never returned to this place.

We descended the other side of our “mountain” and discovered the most shocking, unexpected thing at the bottom. Emerging from the river where it curved around the mountain we’d just climbed over, was a road. A real road. Clear, pronounced, indisputable: a road. We followed it in, surprised, hopeful, amazed, and happy, under a sunset sky and surrounded by the frozen forms of magic. It was a km or two on this straight road to the mountain hut of Básar. We walked into a shockingly modern and well-equipped encampment we’d no idea was there. Boardwalks, BBQs, showers, numerous timberframe buildings, kitchens, and water taps at the campsites. This was especially startling after the day we’d just had, to find this small city where everyone had 4x4s emerging from the mountains and trees.

We descended the other side of our “mountain” and discovered the most shocking, unexpected thing at the bottom. Emerging from the river where it curved around the mountain we’d just climbed over, was a road. A real road. Clear, pronounced, indisputable: a road. We followed it in, surprised, hopeful, amazed, and happy, under a sunset sky and surrounded by the frozen forms of magic. It was a km or two on this straight road to the mountain hut of Básar. We walked into a shockingly modern and well-equipped encampment we’d no idea was there. Boardwalks, BBQs, showers, numerous timberframe buildings, kitchens, and water taps at the campsites. This was especially startling after the day we’d just had, to find this small city where everyone had 4x4s emerging from the mountains and trees.

There was the disappearing bus. There were a dozen jacked up Toyotas and Pajeros, transporting dozens of tour groups. All of them had driven into the river, followed it around the foot of the mountain, and carried on down the road.

We tracked down the warden, paid for our camping, quickly climbed a short trail to a marked summit to have a look around, and set up our tents in a lovely magical dell next to a trickle of bubbly creek.

As it turned out, tour vehicles never pick up non-paying riders; the Italian had been the last passenger vehicle of the day and therefore our last chance at a ride. We weren’t being wimps about the river. It’s almost never this high, but the Króssa was flooded because of the sun on the glacier and the heat of the eruption beneath it we didn’t know about yet. When I talked to the hut guide later (when he picked me up hitchhiking), he shook his head in amazement that we made it that day, and said many tours had turned back, because it was so dangerous in flood. The river had tossed the pedestrian bridge aside and downstream, but the next day the water had much subsided, and the bridge was hauled back into place. It also emerged later that Landmannalaugar was a totally unreasonable goal for one afternoon, and to say the road to Keldur was infrequently traveled is a great understatement. So all in all, we couldn’t have done better for this day.